It's pretty late and I have yet another ridiculously busy day tomorrow, so I'm copping out and posting something I keep meaning to put up and haven't gotten around to yet. Remember

that speech I was supposed to give for CTC's fundraiser back in October that I didn't end up reading because Connor decided to have a

ridiculously long seizure? Several of you have asked if you could read it, so I'm going to just go ahead and put it up here. Ta da!

~Jess

In the fall of 2006, my husband Jeremy and I loaded up our

car and drove the 2,000 mile journey from Dallas, Texas to Fort Lewis,

Washington, accompanied by Connor, our six month old son, and Cricket, our very

carsick cat. I figure since our marriage

survived that car trip intact we’re stuck with each other forever.

Also crammed into the car was Connor’s huge collection of

medical equipment and a steadily growing laundry list of diagnoses. I’d given birth to a medical landmark; our

son had just been diagnosed with a genetic condition so rare he was the only

known case in the world. He has an

unbalanced translocation—where one part of a chromosome is deleted and part of

another chromosome is duplicated, and his particular issue is so rare that it

doesn’t have a proper name—just a dozen word description of where on his genes

the deletion and duplication occurs.

It’s amazing how just a tiny error in the blueprint mapping

out his body could have such dire consequences; Connor has over two dozen

separate medical conditions caused by his genetic issue, affecting nearly every

system in his body. He had his first

surgery at six days old to remove his right kidney, which was swollen up so

large it was bigger than his lungs. His

second surgery to fix his twisted intestines was done two weeks later. Whole swaths of his brain were missing, smaller

or formed differently. He had a heart

condition, visual impairment and hearing loss, and profound developmental

delays.

To make matters worse, at two weeks old he was taken out of

his isolette for a diagnostic test, got too cold, went into shock and one of

the fragile blood vessels in his brain tore, causing him to have a stroke. This did further damage to a brain that was

already struggling. We saw a lot of

grim-faced doctors who used words like “terminal illness” and “brain-stem

response only.” We were told he would

never move his arms and legs with purpose, never recognize us or communicate,

and would almost certainly die in the first few weeks after birth. They were sure he’d never see his first

birthday.

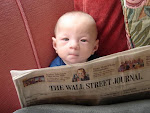

Despite the dire predictions Connor’s condition slowly

improved until he was well enough to leave the hospital. The kid snoozing in the car seat as we wound

our way through the pass in Colorado and headed across Wyoming didn’t look like

he was about to die at any minute. He

looked adorable. He had a button nose,

huge liquid-black eyes that would slowly change over the months to a startling

green, and beautiful star-fish hands with long, tapering fingers. He was also bald as a cue ball and missing

his eyebrows, which had been rubbed off by the hat he wore in the hospital for

his c-pap machine. In my post-pregnancy

emotional state I was nearly as concerned about the eyebrow thing as I was

about his huge list of medical conditions, because I was convinced they would

never grow back and he’d be made fun of in school not because of his

disabilities but because he would be “that kid with no eyebrows.”

So we settled in at Fort Lewis, Jeremy reported in to his

job as an army officer, and I set about the monumental task of figuring out how

the heck to parent this special little guy.

Somehow I hadn’t been issued the magic wand with the ability to fix

everything that I figured most new mothers were handed on the way out of the

hospital, and my liberal arts degree left me woefully unprepared in the medical

knowledge department. I threw away my

copy of What To Expect The First Year after it started talking about how

baby should “have good head control and be pushing up on her hands” and holding

my baby still felt like cradling a tube-sock filled with jello. I felt increasingly isolated and helpless

because I knew I needed to do something to help my son, but I didn’t have the knowledge

or the tools to figure out what to do on my own.

After about a month of waiting on a list, we were finally

able to get Connor in at a program for physical and speech therapy. We attended all of four sessions before the

company abruptly went out of business, leaving Connor and hundreds of other

local children out of services. I put

Connor’s name on the waiting list of every therapy clinic I could find, and a

few days later I got a call from CTC.

They were opening up a clinic in the Tacoma area and doing their best to

help as many families as possible, and they had a physical therapist who could

work with Connor. They’d add speech

therapy in to his regime as soon as they could.

CTC changed our lives.

Connor began working with Laura down in a tiny house located

next to a junkyard that served as CTC’s temporary quarters while they worked on

finding a more permanent area to house their offices and therapy rooms. Soon sessions with Julie, a speech therapist,

were added in, and later on Jolie, an occupational therapist, worked with him

as well. For the next five years Connor

traveled to therapy several times a week, beginning in the little house, then

moving to the upstairs rooms in a church, to their newly renovated building off

of Hosmer, back to the church when the building flooded, and then to Hosmer

again once the repairs were finished. For

the first time, I wasn’t alone—I was surrounded by people who understood how

terrifying and isolating having a child with special needs could be, and who

were eager to help empower me and Jeremy as we navigated our new world.

Under their care Connor began doing things that based on his

medical conditions should have been impossible.

It was there that he reached out and activated a toy for the very first

time. It was there that he first sat on

his own, wobbly but completely unsupported.

He received his first pair of ankle-foot orthotics and learned how to

stand with assistance. He rode his first

pony at a CTC Harvest festival and loved it so much he refused to get off. He began communicating with sign language,

making choices, and allowing me to have a window into how he interacted with

and saw the world. I still tear up

thinking about the first time he signed “Mommy” and reached out for me. I don’t think there’s a more precious gift

anyone could possibly have given me.

Over the years CTC has become a life-line, and its therapists

have become my friends. They’ve thrown

themselves into finding solutions for the unique problems Connor’s conditions

present as they arise. When Connor had

his first-ever seizure and collapsed at a therapy session, they called 911 and

held my hand until the ambulance arrived.

One summer when our unairconditioned apartment reached temperatures too

hot to be safe for Connor, Laura even opened up her home to us so we had a cool

place for him to sleep. It’s not just a

job for them-- they put their whole hearts into helping Connor, and he’s

blossomed as a result. I will be forever

in their debt.

Thank you so much for helping CTC continue to make a

difference in the lives of children like Connor and parents like me. The therapists at CTC couldn’t give me or

anyone else a magic wand to “fix” things—no one can do that. Connor will always be profoundly affected by

his medical conditions. And that’s okay;

he doesn’t need to be “fixed” because he isn’t broken. But what they did do is help Connor become

the best version of himself; to live as happily and as independently as he

possibly can. And they have given me and

hundreds of other parents like me the ability to do something for my child; to help him become that person. The things that Connor has learned at CTC

have profoundly changed his life and mine for the better.

I will be forever grateful for that.